A question from Thailand: Is the platform economy a new face of labour exploitation?

Akkanut Wantanasombut, researcher at the Just Economy and Labor Institute, a Thailand-based organization that promotes social and economic justice through workers empowerment, has been studying the effect of platform-driven economy on service workers in the country.

At a forum titled "Digital Economy And Labour: The Old Crisis Or New Opportunities?", which was organized by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Bangkok in April, Akkanut presented the findings of research he undertook among service workers in Bangkok and Chiang Mai who use smartphone applications to make a living in the transport and hospitality sectors.

We talked to Akkanut about the objective and findings of the research, to be published in Thai by FES, and what actions can help platform workers influence the quality of their jobs.

How did the idea about the research you conducted on the platform-driven economy in Thailand come about?

Four years ago when I moved to Chiang Mai from Bangkok, I experienced first-hand the absence of a proper mass transit system, at the time compounded with the start of operations by Uber. As soon as Uber started operations in Chiang Mai, Uber drivers and those of the “rod songtaew dang” or “rod dang”, the traditional two-row seater, clashed heads on. The conflict almost erupted into violence.

Transportation facilitated by ride-hailing apps became a huge topic in the city. I started to document and report the debates via the online portal Thai Civil Rights and Investigative Journalism, where I also work as the editor. The reports sparked the interest of the public, so we organized a public forum where we invited drivers from both services, as well as the authorities.

Rideshare Controversy Hits Chiang Mai: Uber and Grab car Under Fire

The public opinion was unfairly accusing the rod dang of being the troublemakers, while favouring the usefulness of the Uber services. The rod dang worried for their job security because of limited opportunities for work in the city. In the study, which was supported by FES, I elaborate among other things how those taxi drivers were overcome by this fear and raised their voice as Uber entered the market.

What platform-based services did you look into and how did you go about conducting the study?

We studied platforms in three different sectors: Uber in the transportation sector and also Grab, Airbnb in accommodation, and the Thai platform BeNeat, which provides maid services. We included BeNeat as an example of a Thai platform, to understand how these are influenced by the global ones such as the other three examined.

We interviewed Uber drivers and their competitors—the drivers of the rod dang— and local authorities in Chiang Mai. To get access to the workers I used the services of the apps to establish the first contact. In the case of Airbnb, I attended regular meetings set up by hosts who use this platform to share information.

How were the working conditions in the three cases you studied?

The perception by workers about their working conditions varies across the platforms. Interestingly, almost every informant working as an Uber driver emphasized at the start of the interview how they like the platform, hailing the flexibility of work as an opportunity gained.

I found many interesting cases. For example, several people from the pool of Uber drivers that I interviewed were senior citizens, retired or close to retirement, often working as civil servants. Being able to choose the time they work for the platforms, they see it as a flexible opportunity for additional income. This was a preferred alternative to what they see as dependency in the case of welfare from the state or support from family.

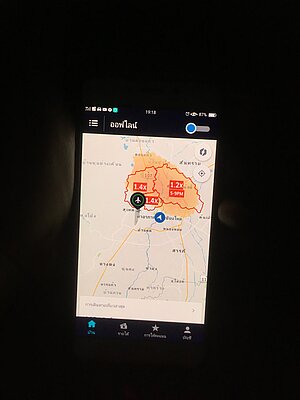

There is a flipside to these benefits. Uber motivates drivers to drive longer hours using incentives, such as bonuses upon completion of, for example, a certain number of drives or servicing in specific times of the day.

One single mother had her four-year old sick daughter on the front seat. She pleaded with me, ‘please don’t report this to Uber’ because it will put her in trouble if she has someone else in the car at the same time as a passenger. She explained that the kindergarten had asked the mother to keep the child at home to prevent infection at school. She had no choice but to take the girl to work because that was the last day to hit a target for a bonus incentive that she had worked on all week.

Drivers hesitate to deny passengers because they worry it will affect the reward-based algorithm behind the platform. They are afraid that if they do not accept ride request, they will lose their chance to get passengers in the future. They believe, the more passengers, the more chance of being awarded high-grade feedback, which in turn improves the chances of getting more passengers.

With the ride-hailing apps, some have to drive for 10 hours without a meal break because the system lines up new passengers before the previous one has even been dropped off. “I have no chance to have lunch, so I have to eat it while I am driving”, one of the interviewees told me. Drivers hesitate to deny passengers because of the reward-based algorithm behind the platform: the more passengers, the more chance of being awarded high-grade feedback, which in turn improves the chances of getting more passengers.

How about the other two cases, Airbnb and BeNeat, what are the platform workers there mostly concerned about?

The greatest concern with BeNeat is the wage. The business pays workers an hourly rate of 180 THB (US$ 5.7), considered high compared to the minimum daily wage of 325 THB (US$ 9.5) in Bangkok. But the platform pushes all the expenses to the platform workers, from transport and equipment to detergents.

For example, working two jobs a day, at the minimum work-hour of the platform which is two hours, the worker could earn 720 THB a day. After deducting all costs, the domestic worker will ideally end up with roughly 500 THB. If the average salary one could earn from conventional employment is nested between 13,000 - 15,000 THB, working on the platform does not really increase their income. On top of this, there is no certainty that the platform workers will receive requests for two assignments every day, and in fact, they do not. All in all, this leaves the platform workers at BeNeat with a daily income that on average barely meets the basic daily wage.

Airbnb is different from Uber and BeNeat, because most of the people who join that platform are property owners. Most of them have other day-time jobs and rely on third-party services to welcome guests and prepare the rooms. New kinds of jobs have emerged because of this platform, which is a positive impact.

In your research, platform workers talk about flexibility of work as a positive feature of their jobs. What is your thought on this? Can we say that the platform economy creates good quality jobs?

I think we need to look at the platform itself separated from the technology behind it. The technology is certainly useful, but the way platforms are used is for the benefit of owners themselves more than anything else by controlling people with the help of an algorithm.

Technology can be used to improve productivity and working conditions, but it seems the platform owners use the technology to exploit users both from the demand side and the supply side, just to have more and more profit.

In the traditional model, only the owners of the resources could benefit from their resources. Platforms have created their own channels to share benefits without owning any resources, through controlling algorithms. For example, I own a house and I have an empty room, right? If I would like to rent out, then I can have someone to rent it and charge for this. But the platform technology allows an entrepreneur, the third party, to see as opportunity, like Airbnb, to create a platform that is able to sell the house owner a service, in the form of access to the market. The platform in this way earns a benefit from the owner’s resource.

In addition to their income from the service, platform owners gain the advantage of being able to manipulate users on both sides of the exchange. They benefit from this, for example, by pushing all the costs and risks to the users. So, I think this is a new type of exploitation, which is unfair, lacks transparency and is irresponsible.

In March, Grab announced that it had acquired the South-East Asia business of its rival Uber. What is the implication for their drivers?

The merger is a very good example of how part of the workings of capitalism today is also about eliminating competition and the making of monopolies, centralizing more power in the hands of the owners of the platform, leaving the users with less control and fewer benefits.

Most of the drivers in Thailand used to have both Uber and Grab. This gave them the possibility to weigh in on either platform and choose between the competing incentives. With the merger this kind of possibility for the drivers and for the passengers is eliminated.

What recommendations do you draw from the findings? What should be done?

In the recommendation I focus on the unfair competitiveness that characterizes the current conditions for work in the platform economy in the three sectors we analysed for the study.

People who participate in platforms like Uber and Airbnb don’t consider themselves employees. For this reason, they don’t see the need for collective action, which has great repercussions on their ability to negotiate with the platform.

In Thailand the government is trying very hard to promote the digital economy, but they pay very little attention to the problems that come with it. For starters, how does one define a private contractor or an employee, and what are the implications of the employment relationship with regards to social security? We need to have a proper law in place to regulate these new forms of employment relationships, and workers’ rights must be protected. More study on the impact of platform economy from various aspects is needed to create suitable regulation at policy level.

We also need to improve awareness of workers’ rights among those working for these platforms In Thailand, people who participate in platforms like Uber and Airbnb don’t consider themselves employees. For this reason, they don’t see the need for collective action, which has great repercussions on the ability to negotiate. The platform owners are aware of this and they try to cut out any multidirectional use of the platform, with workers’ calls to the platform answered by automatic secretary and no possibility for workers to exchange experience with one another.

We need to encourage those people who participate in the platforms to realize that they have a right to negotiate with the platforms and with the authorities. I would like to encourage them to meet each other, exchange stories, and promote collective action. In this way we can draw public attention to other problems that we will also have to face. The Chiang Mai rod dang taxi drivers are just one example of a sector whose fear for jobs security underpins a crucial question: If some service workers need to follow regulations, why should not the competitors have to do the same?

###

Mila Shopova is the regional communications coordinator for FES in Asia. For more information on the upcoming study and the work by FES in Thailand visit the official website of the Bangkok-based country office www.fes-thailand.org and follow the FES Thailand Facebook fan page for latest news.

FES Asia

Bringing together the work of our offices in the region, we provide you with the latest news on current debates, insightful research and innovative visual outputs on the future of work, geopolitics, gender justice, and social-ecological transformation.